Books often serve as saviors for Black women.

Zora Neale Hurston saved my life. I was first gifted Their Eyes Were Watching God at age 16. Hurston’s masterful prose—full of passion and amazing Southern dialect—touched me deeply. I’d spent my childhood indulging in the Sweet Valley adventures of Elizabeth and Jessica Wakefield and the limitless ladies of the Baby-Sitters Club, but for the first time, there was a Black female protagonist who understood me. Her cultural experiences mirrored my own. Sixty-two words on the first page of Their Eyes Were Watching God deepened my adoration of literature and propelled me into life as a scribe.

Books often serve as saviors for Black women. A paltry media landscape offers Black women limited and often stagnant representations of Black female life, so we’re often forced to seek heroines however and whenever they’re available. Literature happens to be one of the few mediums where Black women can see and read ourselves and our experiences through the lens of protagonists who bare resemblance to us.

Pleasure and love are central themes in literature written by Black women and for Black women. Oppression strips us of citizenship and deduces our humanity, but racism and sexism and homophobia and socioeconomic classism can never strip us of our collective and individual joy. Literature, in particular, provides space for Black women to see happiness and triumph, hopefully moving from the pages into our consciousness.

In honor of the Black female protagonist, here are five who have profoundly shaped my conceptualization of love and pleasure, especially as I continue to strengthen my feminist commitments.

Janie Crawford

Janie Crawford

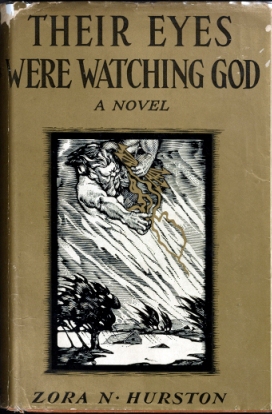

Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston

The protagonist of Their Eyes Were Watching God spends the entire book on a self-exploration of love, pleasure, and happiness. Some of her deepest realizations appear within her romantic relationships, but Crawford embarks on a journey to discover herself at her core. Crawford resides in Eatonville, Florida, a Black township that serves as its own character. The residents of Eatonville are invested in Crawford’s life—especially her love life—and have rigid expectations that she must fulfill in order to be perceived as a respectable woman. Janie Crawford rebels against those norms to establish her independence and claim her happiness.

Lesson: I don’t have to conform, or be the world’s mule.

Sula

Sula

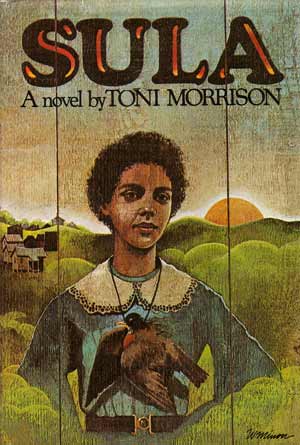

Sula, by Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison is brilliant, and Sula—one of the protagonists in a novel of the same name—is a manifestation of that brilliance. Sula is one-half of a duo. Her childhood best friend, Nel, is her polar opposite, but their love surpasses the boundaries their families attempt to place on them. Nel kowtows. She doesn’t question how her womanhood factors into the expectations of those around her, and instead settles into a conventional role as a wife and mother.

Sula, on the other hand, survives multiple tragedies and decides to leave her small town behind. Sula is considered an outlier. She’s educated, has had relationships that didn’t result in marriage, and refuses to be limited to society’s expectations of womanhood. Sula is unfamiliar to the citizens of The Bottom, so she’s shunned when she returns. Sula and Nel’s husband initiate an affair, which ruins their friendship. Yet Sula’s presumed wildness also elicits harmony within the town. She remains unbroken, and committed to being independent, regardless of others' opinions. As Sula approaches death, she’s able to realize her missteps and correct them, while also accepting that her less-traveled path was best for her.

Lesson: Be who you are, no matter how it is perceived by society.

Clarice "Precious" Jones

Clarice "Precious" Jones

Push, by Sapphire

Push was the first book that was difficult for me to read. I picked Push up and put it down multiple times before I was able to finish it. Clarice "Precious" Jones’ pain—which includes sexual, emotional, and verbal abuse from her parents, as well as the contraction of HIV and illiteracy—haunted me each time I attempted to read her story. Precious’ world is so dark, and was so different from my own. Each chapter illuminates Precious’ agony, but also highlights her progress. Precious refuses to be defeated. She leaves her poisonous home and begins educating herself. She surrounds herself with supportive figures who offer her and her children guidance as she attempts to piece her life together. In each chapter, the grammar improves, which is a literary device that allowed me and other readers to see how Precious is improving her reality. In the end, Precious still has many demons to conquer, but I was most inspired by her triumphs.

Lesson: Life’s circumstances should never dictate happiness. You are in control.

Celie and Suge

Celie and Suge

The Color Purple, by Alice Walker

I first attempted to read The Color Purple when I was 14. I was a voracious reader, and even I couldn’t grasp the magnitude of Alice Walker’s phenomenal masterpiece. It wasn’t until I reread the book as a senior in college that I was able to understand the feat Walker accomplished by publishing a novel that chronicles friendship and love and triumph through the lenses of multiple Black women.

At the beginning of the book, Celie is constructed as the classic victim of both patriarchy and abuse. She is raped and impregnated by her father, who also successfully silences her by telling her that nobody but God can know he’s abusing her. Unintentionally, Celie’s father also gives her voice; she begins writing detailed letters to God about what she’s experiencing and what’s happening in the world around her. Celie’s father then sells her to an abusive man who wants both a wife and a servant; he is also abusive toward Celie. Celie’s hurt is facilitated by her father and her husband.

In contrast, Shug is untamed, wild, and brings chaos into Celie’s life and home. Shug is the love of Celie’s husband’s life, but the world makes little space for such a free Black woman. For Shug, an irreconcilable split with her preacher father is her punishment for being liberated. Shug’s father disowns her and removes her children from her custody, so she attempts to make herself “respectable” by getting married and leaving her jazz-singing lifestyle behind.

When Celie encounters Shug Avery, she begins to discover that she can exist outside of her husband’s abuse. Initially, Shug is unkind to Celie. She calls her ugly when she first meets her and ignores Celie. However, she eventually learns to love Celie, especially as the latter begins caring for her. As Shug recovers from a venereal disease, Celie prepares meals for her, brushes her hair, and listens to her stories about a turbulent life that’s included much pain. Their bond is strengthened as Shug strengthens. Once Shug is at full stealth, she begins repairing Celie’s broken spirit. When Celie’s husband, Mr. ____, brings her to the juke joint, Shug sings a song of solidarity to Celie. Shug prepares a song called “Miss Celie’s Blues,” an ode to her being able to see Celie in the totality of who she is.

In “Miss Celie’s Blues,” Shug refers to Celie as “sister,” which signifies their kinship. That bond assists in liberating Celie from the oppression of her partner. This leads to minor acts of resistance, like Celie’s decision to spit in her father-in-law’s glass of water after he insults Shug. There’s also the assumption that Shug and Celie spark an intimate relationship that frees her sexually as well.

Shug tells Celie she’s beautiful. She tells her to smile. She begins lifting Celie up, which gives Celie the strength to heal. Their friendship, and eventual relationship, is built and sustained by love and resilience.

Lesson: Be free, and find women to be free with.

Ifemelu

Ifemelu

Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

I’ve read, and reread, and reread Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah since its release in 2013. The principle character, Ifemelu, is who I aim to be. She’s fearless, honest, committed to pursuing pleasure, and a gifted writer. Ifemelu is Nigerian, but ventures to the United States to complete her education. In the United States, Ifemelu is forced to grapple with her Blackness for the first time, as she also attempts to heal after separating from her childhood love, Obinze. She locates contentment as a popular blogger and live-in partner to a college professor, but is still unsatisfied. Instead of remaining in a state of contentment, Ifemelu chooses to pursue bliss by returning to Nigeria and rekindling a romance with the now-married and rich Obinze. I see so much of myself in Ifemelu, especially as I consider my future as both a writer and a teacher.

Teaching affords so much comfort that writing can’t, but writing is my passion. Approaching that crossroads is less tense when I have the fictional, but relatable, journey of Ifemelu to guide me.

Lesson: Don’t settle for content. Go for unlimited bliss.